Their members come from all over the country. They have different preferences as to which retailers they frequent. The extent of their activity varies from snagging a few illicit freebies, to getting cartloads of items for next to nothing. But there’s one thing that an alarming number of coupon “glitch groups” on Facebook seems to have in common – when it comes to committing coupon fraud, the controversial coupon app QSeer is their tool of choice.

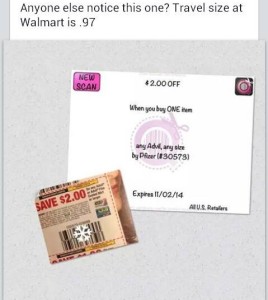

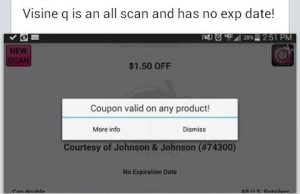

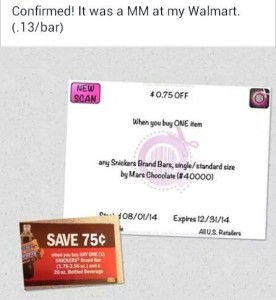

Click to enlarge any of the examples below, of glitch group members gloating about their finds – a coupon for an 80-count bottle of Advil that will “work” on travel-sized containers. A coupon on Snickers and a bottled drink that doesn’t actually require a drink purchase. And a Visine coupon that will supposedly grant a discount on anything in the store.

All of this was, and is, going on in “secret” and “closed” Facebook groups that the coupon industry has been working to shut down. “Decoding” a coupon in order to use it on a product for which it’s not intended – especially when that misuse results in getting products for free, or getting cash back – is akin to shoplifting, the industry argues. So Facebook has deleted a large number of groups, in which many members use QSeer, advocating this kind of coupon misuse.

But if the industry is pressuring Facebook to put a stop to this activity, should QSeer also be trying to put a stop to the apparent misuse of its product?

That depends on whether QSeer considers it “misuse” at all.

QSeer debuted in 2013, promoting itself as “a breakthrough product that allows coupon shoppers to read and interpret the new system of bar codes that is being used on manufacturer coupons.” The app allows users to scan coupons’ complex DataBar bar codes, which have largely replaced the old-style, less-complicated UPC bar codes, and reveal in plain English how the coupons are coded.

“Our motivation to create QSeer was to enable consumers to determine whether their coupons contained hidden tracking codes that manufacturers use to gather personal details regarding shopping behavior,” QSeer co-founder Brad Carey told Coupons in the News. Other coupons may be coded not to double, without saying so on the coupon itself, or may be incorrectly coded so they won’t scan correctly even when used properly.

But early adopters soon found other uses for the app – scanning all of their coupons to see if any incorrect coding could be exploited to their advantage. A coupon may state that it’s valid on a particular product, but will scan and be accepted on any number of other products from the same manufacturer.

What do QSeer’s founders think about this? It depends on which of their statements you read.

The app’s legalese states that it makes “no moral judgment or redemption suggestions” and “is not designed to be used as a vehicle for the misredemption of any coupons.” The FAQ on QSeer’s website goes further, notifying potential users that “when you redeem a coupon, the manufacturer has to pay the retailer for the cost of redeeming that coupon. The manufacturer expects to sell the product shown on the coupon in order to have profits to cover the cost of the coupon. So please use these coupons responsibly and only on the items pictured or described in English on the coupons.”

But in other places, the tone is markedly different. “Some coupons are coded to give you a discount off your purchase of any item in the store!” the FAQ on the app itself reads. “The bar code does not require you to purchase the item described on the coupon. You do not even need to purchase an item from the manufacturer listed on the coupon.” And from elsewhere on the QSeer website: “QSeer tells you what products are required according to the coupon’s barcoding. What you do with that information is up to you!”

Wink, wink.

QSeer’s founders insist that encouraging coupon abuse is not their motivation. But if it happens, well, maybe that will get the industry’s attention. “Why are people able to game the system today?” Carey asked. “It’s only because manufacturers (or their vendors) do not take the time to construct their DataBars properly to eliminate ambiguity and errors.”

Carey said a recent check of a set of Sunday coupon inserts revealed that 68% of the coupons’ DataBars contained a “serious error,” which he defined as anything that would “allow for the coupon to be redeemed in a manner other than the manufacturer’s intent as per the English words, or cause the coupon to be falsely rejected at point of sale when the consumer had met the stated terms.”

QSeer’s philosophy is that couponers have the right to know if their coupon is going to be rejected at the checkout, even when they buy the correct product as described on the coupon. But, as evidenced by QSeer references in the Facebook glitch groups, other users have twisted this to work in their favor. They’ll exploit DataBar errors and omissions, by scanning a coupon to find out what it will “work” on. Then they’ll purposely use the coupon incorrectly, on a product for which it’s not intended, and share their discovery with other coupon “glitchers” in their groups.

While the coupon industry has been relatively open about its opposition to the glitch groups, it’s remained largely silent about the glitchers’ use of QSeer, and about QSeer itself. A number of coupon publishers, coupon issuers, the Coupon Information Corporation and even the company that administers the DataBar system in the United States would not offer any opinion about QSeer when asked by Coupons in the News.

Surely, their silence does not signify tacit approval. So why not take a more forceful stand against the misuse of the app – or against the app itself? “We don’t provide perspective on apps,” a representative for one major manufacturer said.

Okay then. Remember that the next time you want the coupon industry’s perspective on Candy Crush.

At any rate, the industry’s public silence means that QSeer and its supporters’ voices are outweighing those of its detractors. And publicly at least, QSeer disavows the abusers. “As with any product, there are a small percentage of users who navigate to a usage that is unintended and inappropriate,” Carey said. “The fact that some write bad checks doesn’t condemn check printers, or that some assaults are made with hammers doesn’t mean that Home Depot should stop selling those important tools.”

Of course, neither does it mean that Home Depot should put FAQs on its hammers stating that they “may” be used to hit someone over the head, but that the store “advises against it.”

Wink, wink.

Still, “there are currently thousands of QSeer users who want exactly what the product is designed to do, and that is to help them to understand and comply with coupon terms in a confusing new digital environment,” Carey argued. “The vast majority of QSeer users are honest, hard-working couponers with no affinity to the small group of abusers.”

And as a way of demonstrating their good intentions, QSeer’s founders have introduced a new app. CHEQR is a “professional” version of QSeer that’s geared toward coupon issuers. It points out specific faults in coupons’ bar codes and suggests ways they can be coded more accurately. That way, the thinking is, the abuse of coupons – and of QSeer itself – becomes a moot point.

Until then, “the existence of coupon abusers is unfortunate but is nothing new,” Carey said. “They existed when we only had UPC-A codes, and they existed even before the advent of coupon bar codes.”

But now that there’s an app for that, decoding and abusing coupons has never been quite so easy. Knowledge may be power – but too much knowledge can sometimes prove to be a dangerous thing.

I wouldn’t quote or use CIC as a reference. It is a phony BS website

Yet CIC, while working with the authorities, have stopped incidences of coupon fraud.

You must be one that exploits coupons.

Stores should have cashiers go back to reading all the coupons.

Ain’t nobody got time for that!

Thank God where I am in Canada, coupons are not scanned.