(Be sure to read this followup story: “Retailers Rebuff Snipsnap: So Is This App Ill-Advised, or Illegal?”)

It seemed like a good idea at the time – a mobile app that promises to transform paper coupons into digital coupons, allowing users to take advantage of discounts without having to mess with those pesky scraps of paper. Now, more than a year after its launch, the couponing app SnipSnap has suddenly found itself in the spotlight – earning both praise and intense criticism. Some, like Katie Couric and Dave Ramsey, are hailing it as a revolutionary new idea, while others are accusing it of aiding and abetting outright coupon fraud.

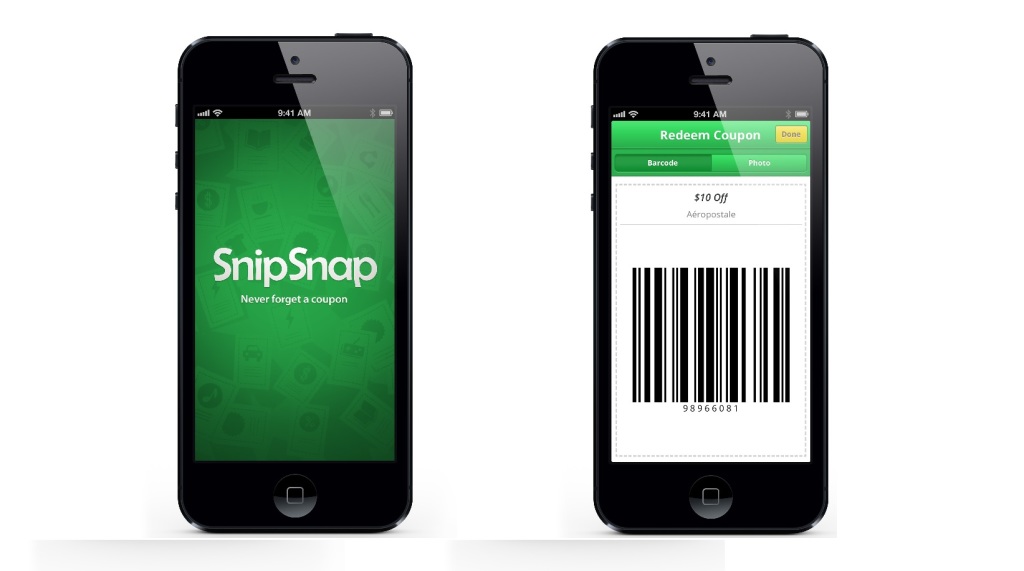

So what is SnipSnap exactly, and what is it that’s prompting such opposing reactions? In its own words, “The SnipSnap app allows anyone to convert a printed coupon into a digital, mobile format, which they can easily search and retrieve on their smartphone. All a user needs to do is snap a picture of the offer… and the app works its magic to scan all of the printed text and images.”

In other words, just take a photo of a coupon, and redeem that instead of the actual coupon. Could that possibly even work?

SnipSnap’s CEO said it worked for him. Ted Mann, a self-professed “tech guy” and not a “coupon guy”, told Coupons in the News that he was never the couponing type until he had his first child – and found himself paying full price for diapers while valuable coupons for Babies “R” Us sat forgotten and unused at home. So he figured, why not take pictures of the coupons with his iPhone, so he’d always have them handy? “And in every store, it worked,” he said. Cashiers and managers were apparently okay with scanning the coupons off his iPhone, and they claimed that “everybody does it.”

So Mann turned his idea into an app, and SnipSnap was born.

There’s a whole lot more to the story, but first take note of a couple of massive red flags. Taking a photo of a coupon and presenting it as an actual coupon, is akin to photocopying it in many couponers’ minds. And the defense that if “it worked”, it must be okay, is one that fell out of favor after certain extreme couponers were exposed for exploiting loopholes and weaknesses in the system. In fact, SnipSnap users are even able to report whether a coupon “worked”, giving other users an idea of its success rate before they try it.

But more on all of that later.

A key decision in the development of the app, which proved to be “a crucial and controversial decision,” Mann said, was the ability to share coupons uploaded to the app. So not only can users store digital copies of their own paper coupons, they can make those scanned coupons available to all other users. In fact, you don’t have to upload any coupons at all in order to use the app – you can just search through coupons that others have loaded. Sites like RetailMeNot, which aggregates coupon codes for online shopping sites, helped to “pave the way for coupon sharing,” Mann said.

With SnipSnap, though, it’s not about sharing coupon codes, but sharing actual coupons. Copies of actual coupons, that is. Need one of those “20% off” Bed Bath & Beyond coupons? No need to wait for one to appear in your mailbox – they’re on SnipSnap. Forgot to save the coupons in the latest Walgreens sales circular? No worries, they’re on SnipSnap. Didn’t receive a Target coupon booklet that was sent to select customers? Doesn’t matter, all the coupons are on SnipSnap. You weren’t one of the lucky few to be mailed a special coupon for a free item at Victoria’s Secret? Get all the free stuff you want – the coupon was available for all to use on SnipSnap.

For now, the app is meant to be used only for retailer coupons. And some retailers are happy to be on board, according to Mann. Stores like Bed Bath & Beyond, Aeropostale and Kmart pay a commission to SnipSnap for any coupons used via the app, and they pay for the privilege of being included as a “suggested coupon” passed on to users. Partner retailers are also able to exercise a greater amount of control over their coupons, identifying which ones are meant to be single-use, for example, or which ones are only meant for specific customers.

As for the retailers who are not partnered with SnipSnap, “some of them are not thrilled with what we’re doing,” Mann admitted. Target, for one, has expressly stated that it does not accept coupons presented via SnipSnap. “Coupons are void if copied, scanned, transferred, purchased, sold, prohibited by law, or appear altered in any way,” a spokesperson said in a terse statement to Coupons in the News. “Therefore we do not accept coupons in this app.” When asked how Target plans to enforce its stand, the spokesperson merely noted that “Target routinely works with our team members to provide comprehensive training,” suggesting that the onus is on cashiers to know well enough to reject coupons from SnipSnap.

That’s tough to do, since another feature of the app creates new, “clean”, mobile-optimized bar codes. Even the most amateurish, poorly photographed coupon (like the “exclusive store coupon” for free frozen fruit at Kroger, pictured at left) is transformed into a nice-looking, easily scannable bar code (pictured at right), with no indication that it was generated by a third-party app. So anyone who manages to successfully use a SnipSnap coupon at Target, has by definition gotten their cashier to violate Target policy.

Mann’s response: “Is it in violation of its policy? I suppose. Does that mean you shouldn’t do it? Not really.”

Many stores’ coupon policies are “flexible,” Mann claimed, noting that “the world is changing” and more shoppers are going digital. He said SnipSnap is just a recognition of that fact, and he has no ethical concerns with it, as long as the “goal of the coupon” is the same, and the app “honors the spirit in which the coupon was issued.” Furthermore, if Target asked him to remove its coupons from the app, he would. And so far, it hasn’t.

At least one national retailer has. But their coupons continue to show up on SnipSnap. When contacted by Coupons in the News for this story, the retailer did not want to be identified, but noted that they did not authorize their coupons to appear on SnipSnap, will not accept them and have asked that they not be made available on the app.

“We’ve done our best” to ensure that unauthorized coupons do not appear on SnipSnap, Mann said. That applies to manufacturer’s coupons, too. But, just like the coupons from the retailer that wants no part of SnipSnap, manufacturer’s coupons continue to show up on the app as well.

And that’s what helped to unleash a firestorm of protest in recent days. Growing complaints on SnipSnap’s Facebook page that certain retailers wouldn’t take their SnipSnap coupons, turned to questions about whether the whole thing was a big fraud. Blogger and nationally syndicated coupon columnist Jill Cataldo followed up with a lengthy missive on her website. “What could possibly be wrong with this?” she wrote. “Everything.” Readers sent her dozens of screen caps of manufacturer’s coupons hosted on the app. “Clearly, there is no automatic safeguard in place to prevent manufacturer coupons from being uploaded,” she asserted. The availability of manufacturer’s coupons, despite the app’s purported safeguards, together with the unseemliness of making digital copies of paper coupons, led her to conclude that “SnipSnap encourages fraud on an enormous level… It truly is the digital equivalent of making photocopies of coupons.”

Mann insists his app is “not meant to beat the system.” He considers SnipSnap to be something like the iTunes of the coupon world – creating partnerships with companies to help bring an analog industry into the digital age. And if any non-partnering retailers or manufacturers object more strenuously than they have thus far, perhaps to the point of litigation? Mann claims protection under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which grants certain third parties safe harbor from any “allegedly infringing activities” on the part of users. In other words, if it’s illegal, its the fault of SnipSnap’s users, not the fault of SnipSnap.

To expand upon Mann’s own comparison to iTunes, it’s worth noting that iTunes’ notorious predecessor, Napster, also claimed safe harbor protection – and failed spectacularly. You’ll recall that Napster users utilized the service to share copyrighted music with others who didn’t own it and hadn’t paid for it. A federal court ruled that Napster could indeed be held liable for infringement of the publishers’ copyrights. Napster ultimately paid tens of millions of dollars to settle the case, and faded away shortly thereafter.

It’s an imperfect comparison, since coupons are not music, and SnipSnap is not Napster. But neither is it iTunes. And even a few techies who praised the app upon its release way back in May 2012, saw signs of trouble ahead. While TechCrunch blared, “Forget Those Scraps Of Paper, SnipSnap Lets You Save And Share Coupons From Your iPhone,” and the Apple news and review site iMore urged readers to “Say goodbye to carrying stacks of coupons with you everywhere you go,” the website appolicious called SnipSnap “an interesting concept for savers, but likely won’t pan out… The group pool feature is likely crossing a line that companies won’t be happy about.”

You can certainly say that again.

sooo in using your logic….can i take a picture of a hundred dollar bill and pay with that? i run a restaurant. we put coupons in the sunday paper we need the actual coupon to balance our books…same as cash. a copy of a coupon on someones phone does not do it. by the way, we do offer actual digital coupons that we do take also.its not right to double dip…

Pattii I must respectfully disagree with you. Your logic does not seem to be logical to me at all. The problem with many people that “run” businesses nowadays is they have no idea what the customer wants, they are not adaptive, and they don’t know what marketing is if it jumped up and forced money into their bank account.

First off, you mean to tell me that you can’t balance the books properly if a few extra coupons/new or repeat customers decide to visit your establishment?

Second, I scan my credit card with apps and use Apple Wallet so I would say that yes I take pictures of my hundred dollar bills and digitally purchase items.

Finally, I would like to give you an example of the success that “fraud” can have on an entire industry. I’m sure you have heard of Microsoft. Them including countless other companies get software pirated all the time. A study revealed that when the new updates would come out they had a 90% conversion rate from the users of the pirated copies to the authentic licences version. Numerous poles also showed that if those customers did not use the free copy they would never have purchased a license because they would not have understood the value of the product having never used it.

“Taking a photo of a coupon and presenting it as an actual coupon, is akin to photocopying it”

So what? Coupons are rarely one-shot deals any more. Cashiers routinely give me back my paper coupons so I can re-use them as many times as I want until they expire. It usually isn’t even necessary to have the coupon, just the barcode number, which the cashier will enter manually.

The paper coupon is mostly a sales ad that alerts shoppers of the discount, and a convenience for the cashiers, who can scan the coupons to apply the discount. Paper coupons with barcodes replace the old, unreliable method of entering the discounts into the store’s computer system. Then the store’s system was “supposed to” register the discount when the item was scanned, but often was not. The only reason you need the coupon/bar code is that many such sales are intended to be limited to coupon recipients. They are rarely intended to be limited to one-time use.

So Target is a dinosaur; we knew that already. If their management had a clue about computers, my credit card company wouldn’t have had to freeze the credit card I used at one of their stores. Sounds like the author is cut from the same mold, with little to no knowledge of or experience with the modern-day use of coupons, and therefore is unqualified to comment on the app. No wonder they didn’t have the nerve to sign their name to the article.