At first, it looked like a bout of bad online publicity for a popular coupon platform. Now it’s turned into a major legal headache for the suddenly-controversial online coupon code finder.

A total of nine online content creators have now filed four separate lawsuits against PayPal, the owner of the Honey browser extension, just a couple of weeks after a YouTuber released a viral video calling Honey “one of the most aggressive, shameless marketing scams of the century.”

The first of the lawsuits, all of which were filed in a California federal court in recent days, accuses Honey of engaging in “predatory and unfair conduct,” for allegedly operating a business model that swaps out internet influencers’ online referral codes for its own. The second lawsuit echoes those claims, saying Honey “steals credit for sales and pockets commission money it did not earn.” The third piles on, calling Honey a “scheme” that “wrongfully captured millions of dollars in affiliate marketing commissions.” And the fourth and, so far, final lawsuit says Honey’s entire business “is built around stealing those commissions.”

All of the lawsuits rely heavily on the allegations made by MegaLag, a YouTube creator from New Zealand who identifies as a tech investigative journalist. A few days before Christmas, he posted a 23-minute video entitled “Exposing the Honey Influencer Scam,” which now has more than 15 million views. In it, he revealed the results of “a multi-year investigation” that led him to conclude that “Honey is a scam,” for allegedly stealing referral commissions from online influencers and deceiving consumers into thinking they’re getting the best deals possible.

The lawsuits focus on the alleged harm to influencers, who claim to have lost millions to Honey’s “deceitful and clandestine methods.” The initial lawsuit was filed by five YouTubers’ production companies – Sam Denby’s Wendover Productions, artist Ali Spagnola’s Businessing, vocalist Elizabeth Zharoff’s Charismatic Voice, Sean Cannell’s Clearvision Media and Andru Edwards’s Gear Live Media.

Those five, appropriately enough, teamed up with another YouTuber – attorney Devin Stone, who posts videos as LegalEagle, and who filed the lawsuit on his fellow creators’ behalf. He announced the litigation in his own video, entitled “I’m Suing Honey.” “I believe that Honey lied to consumers about what it offered,” he said. “And I believe that Honey lied to creators about what it was doing.”

His lawsuit explains that the plaintiffs earn “substantial revenue” by promoting products and services, inviting their followers to click on the promotion, and earning a referral commission if the click results in a sale. “This is the online equivalent of a salesperson being acknowledged that they helped a customer when the customer goes to the cash register (and receiving a sales commission for the help they provided),” the lawsuit says.

But what if that salesperson “gives you his referral card, you get to the checkout, and right as you’re about to pay, a sleazy salesman pops up going, ‘Hey, should I check if I have any coupon codes for you?'” MegaLag said in his video. While searching for coupons, “he snatches your referral card” and “hands back his own,” and ends up getting credit for the sale.

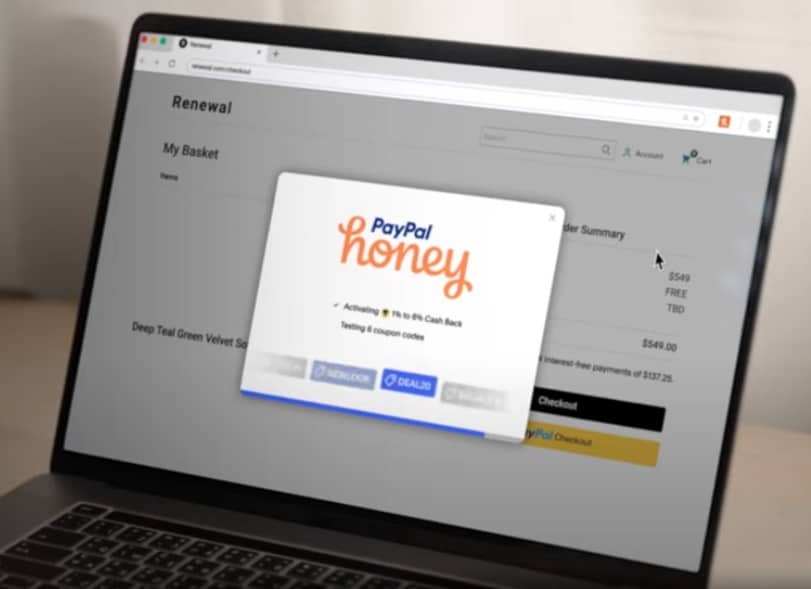

That’s what MegaLag, and the subsequent lawsuits, accuse Honey of doing. Honey was founded in 2012, and purchased by PayPal for an eye-popping $4 billion seven years later. It promises to “automatically find and apply coupon codes at checkout with a single click.” Users who install the browser extension see a popup window when shopping online, inviting them to click to find and apply the best available online coupons.

But as soon as they click, Honey becomes the referrer and earns a sales commission, regardless of whose recommendation led the shopper to that particular merchant’s site in the first place. “The industry refers to this practice as ‘last click attribution’,” the first lawsuit explains, in which the owner of the last affiliate link to be clicked before a purchase gets credit for the sale.

So “PayPal gets credit for the referral and ultimate purchase of the product even though it did not help the online shopper identify the product,” and even if it fails to find any valid coupons, the second lawsuit points out. That lawsuit was filed by Eli Silva, who runs the website Deep Discounts Club, and Ashley Gardiner, whose website is Once Upon A Minivan. While last-click attribution “means the last click determines who gets credit for a sale… the Honey browser extension is purposely designed to exploit the last-click attribution process,” enticing shoppers to click on the Honey button even if it has no discounts to offer, just so Honey can earn the commission for any sale, the lawsuit alleges.

The third lawsuit was filed by GamersNexus, which provides computer hardware analysis, reviews and affiliate links on YouTube and its own website. “PayPal uses every possible artifice to get the consumer to click on their artificial referral button to steal affiliate commissions,” that lawsuit alleges. The last lawsuit, as of this moment, was filed by Instagrammer Claudia Jayne Young, who argues that “while Honey is purportedly providing users with ‘free’ coupons, it is doing so at the expense of affiliate marketers.”

“Ironically,” the Silva and Gardiner lawsuit notes, “PayPal’s business model involves recruiting unsuspecting content creators and influencers to promote the Honey browser extension to their audiences, thereby allowing it to divert commission payments from affiliate marketing links those same content creators and influencers rely on to earn money.”

That fact in particular got MegaLag’s goat, as he implicitly critiqued influencers for entering into business deals to promote Honey, without ever looking into its business model. “I hate to break it to you, but your favorite influencers sold you a lie,” he said.

But “this scam runs much deeper than stolen affiliate commissions,” he went on. Consumers, too, are affected. While the lawsuits all focus on the affiliate commissions the plaintiffs say they lost to Honey, MegaLag told shoppers that Honey “sold you the lie that they would find you every working coupon code on the internet and apply the best one to your cart.” Instead, in many cases, Honey partners with online merchants and offers the coupons they’d like Honey to recommend. “Honey told businesses, ‘Hey, if you partner with us and pay us an affiliate commission, we’ll let you control which discount codes are shared on our platform, and we’ll tell our consumers we scoured the internet and found them the best deal possible’,” MegaLag said. “Everybody wins – just not the consumers.”

PayPal says the company will “vigorously” defend itself against the lawsuits. “Honey is free to use and provides millions of shoppers with additional savings on their purchases whenever possible,” a company spokesperson said in a statement. “Honey helps merchants reduce cart abandonment and comparison shopping while increasing sales conversion. Honey follows industry rules and practices, including last-click attribution.”

The plaintiffs may consider last-click attribution to be unfair. But they’re going to have to convince a jury that it’s illegal. And the defense could use their earlier example against them. Say a salesperson entices you into a store to browse, and they hope to earn a commission if you buy something. Then an employee inside recommends a particular product and you bring it to the register – now that salesperson is eyeing a commission. You change your mind at the register, but then the cashier offers you a coupon and closes the deal – now the cashier feels entitled to that commission. Who deserves it? Last-click attribution would give it to the last person you interacted with, regardless of who first got you into the store.

Honey sees itself as that last person whose coupon got you to make the purchase, and who therefore deserves the commission. Honey does disclose to users that it “makes commissions from our merchant partners,” which is how it stays in business – if it can’t earn money, it can’t save you money. And while it may not always come back with the best, most valuable coupon available, casual couponers benefit from avoiding the hassle of having to go search for a coupon themselves. That may well be Honey’s defense: last-click attribution is an accepted industry standard. Effortless savings are better than no savings. And without following the business model that the plaintiffs decry, Honey wouldn’t be able to stay in business and offer anyone any savings at all.

That would be just fine with LegalEagle, who called out other coupon browser extensions and suggested that none of them should be allowed on Apple and Google’s extension marketplaces. “Enough is enough,” he declared.

Each lawsuit accuses PayPal of a variety of legal violations, including unfair competition, unjust enrichment and deceptive trade practices. Each seeks class-action status on behalf of all other internet influencers engaged in affiliate marketing – everyone from YouTubers to coupon bloggers – who may have lost referral commissions to Honey. And each seeks millions in potential damages.

Neither seeks redress for Honey users who believe they could save more by searching for their own coupon codes instead of relying on Honey. But that’s another story – and, if anyone is so inclined, another potential lawsuit.

Image source: PayPal Honey