Over the past few months, dozens of online influencers have had a lot to say about several online coupon browser extensions they claim are a “scam,” “deceitful,” “a lie” and are stealing money from them. The owners of the coupon-finding tools have largely remained silent.

Not anymore.

Capital One has come out swinging, in the first formal response from one of the half dozen coupon browser extension providers named in more than 60 lawsuits so far. In a motion to dismiss the now-consolidated case brought against it by more than two dozen plaintiffs, the company defends its Capital One Shopping tool, and schools its accusers about “how online shopping (and) the online advertising industry works.” The lawsuit “not only misrepresents the industry,” Capital One argues, “it also amounts to a naked attempt to stifle competition in the marketplace” and “limit the choices of merchants and consumers alike.”

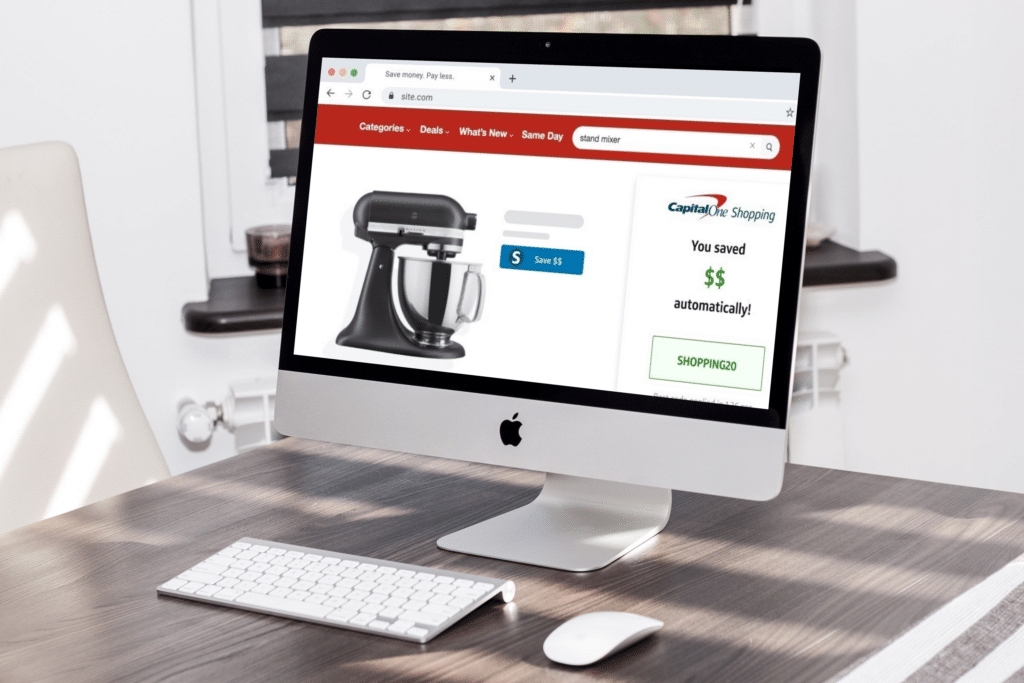

The industry-wide dispute began late last year, when several YouTubers sued PayPal-owned Honey, accusing it of engaging in “predatory and unfair conduct” by allegedly appropriating their sales commissions. Honey offers to search for online coupon codes with the click of a button. It also partners with advertisers and earns a commission if a user makes a purchase. Many influencers also partner with advertisers to recommend products to their followers. If a shopper who clicks on one of their referral links buys the product, the influencer earns a commission. But if that shopper subsequently clicks on Honey’s popup looking for a coupon, Honey gets the credit and the commission.

The plaintiffs claim this is unfair. And over the next few months, dozens of others filed similar lawsuits against Capital One, Microsoft Shopping, RetailMeNot, Rakuten and Klarna, all of which promise to search for coupons or offer other rewards to shoppers who click on their popups.

And now Capital One has become the first defendant to respond in court. “Capital One Shopping benefits, and does not harm, the consuming public,” it argued. But “this case is not about consumers or merchants. Rather, it is brought by Capital One Shopping’s competitors in the online marketing industry,” who claim “they are ‘entitled’ to be paid the entire commission for an online sale if they had any touchpoint in a consumer’s purchasing journey.”

That’s not how it works, Capital One’s court filing explains. “It is up to merchants to decide who gets credit for a sale and how to distribute that credit… it is not ‘stealing’ if a merchant adopts an attribution model that gives a later-in-time publisher credit for a sale.”

Besides, the plaintiffs “offer nothing but mere speculation that they have lost commissions due to merchants’ decisions to partner with, and consumers’ decisions to use, Capital One Shopping,” the filing continues. Furthermore, the plaintiffs “incorrectly assume that any consumer that clicks on their respective affiliate link will complete a sale” and that they are owed a commission at all.

A shopper who uses Capital One Shopping’s browser extension might decide to make a purchase only because they found a coupon by doing so. Or, if they can’t find a working coupon, they might make a purchase knowing that they’re already getting the best deal. The influencers, then, can’t claim they’re “owed” a sales commission for recommending a product, if they can’t prove their recommendation alone led to a sale, Capital One argues.

Some of the plaintiffs’ arguments have focused not so much on how the system works, but how Capital One Shopping and others are allegedly exploiting that system, to its advantage and their detriment. “Capital One has designed its browser extension in a manner that requires users to actively engage” with it, one of the plaintiffs argued. A click equals a potential commission, so the influencers claim the coupon browser extensions are incentivized to do whatever it takes to get a user to click on their popups, in order to redirect commissions from the influencers to themselves.

Capital One’s response was filed before Google announced a new Chrome Web Store policy, which mandates that any coupon browser extension must provide “a direct and transparent user benefit” and can’t claim a sales commission “if no coupon or discount is found.”

But the court filing pre-emptively argues that a Capital One Shopping user “always gets something of value — either a coupon or rewards — for having used the browser extension.” That’s true even if a user is shopping on a site not affiliated with Capital One at all – Capital One shopping will look for coupons even for merchants who offer it no commission for doing so. “In contrast,” Capital One notes pointedly, “Plaintiffs do not allege that they provide any discounts, price comparisons, or other tools or monetary benefits or incentives to consumers” – they provide only sales pitches in order to collect commissions for themselves.

Capital One is asking the court to dismiss the case, noting that it contains mere “cookie-cutter allegations,” “copied and pasted” from lawsuits filed against some of the other coupon browser extension providers. In the end, the company argues, the dispute over claiming commissions comes down to simple competition. And “competition for consumers’ purchasing dollars and merchants’ advertising dollars” is what “fuels the online marketing industry.”

The plaintiffs might add that it’s about “fair” competition. At least one defendant is arguing there’s nothing unfair about what it offers. It will now be up to the courts to determine whose argument ultimately wins out.

Image source: Capital One Shopping/Mockuper