There is a perfectly rational explanation as to why someone would stuff coupons into a cement mixer and give them a spin, before submitting them for reimbursement and telling manufacturers they came from stores where they were not actually redeemed.

That’s some of what will be heard in a Wisconsin federal courtroom, as a multi-million-dollar coupon fraud trial nearly a decade in the making, finally gets under way.

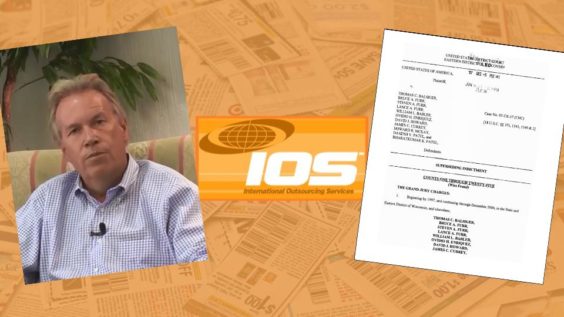

Proceedings began yesterday in the trial of former coupon industry executive Chris Balsiger. He’s charged in connection with his role in what federal prosecutors call the largest coupon fraud case of its kind, which they say cheated manufacturers out of some $250 million. As the former CEO of coupon processing company International Outsourcing Services (IOS), Balsiger oversaw the collection, sorting and invoicing of coupons redeemed at various retailers, in order to secure reimbursement from the manufacturers.

In a federal indictment issued back in 2007, Balsiger and ten colleagues were accused of conspiring to submit coupons for reimbursement that were never actually used by shoppers. Over the many years it’s taken to bring this complex case to trial, ten of the eleven defendants have reached plea deals with prosecutors. Now, most of them are expected to testify against Balsiger – the last man standing. Balsiger is representing himself in what will now be a bench trial – which means no jury will be seated, and the judge will be the one to render a verdict.

In their opening statements yesterday, both sides laid out their key points of disagreement, which include IOS’s contractual agreements, the acceptance of “gang cut” coupons – and that cement mixer.

Contractual vs. Criminal

The crux of the prosecution’s argument is that IOS arranged to cut out extra coupons, mix them in with coupons submitted by retailers, turn them all over to manufacturers for reimbursement, and then pocket the value of the extra coupons – roughly a quarter billion dollars worth – even though they were never actually redeemed in any store. Prosecutors say many of the unredeemed coupons were supposedly “submitted” by smaller, independent retailers, but were invoiced as though they came from larger retailers, in an effort to evade detection.

Balsiger argues there was nothing sinister about mixing coupons from different retailers. “Since IOS owned the coupons, IOS was free to follow its own internal invoicing practices,” he wrote in a pretrial motion. “The prosecution’s basic premise is that it’s ‘unlawful’ for IOS or any retail processor to mix coupons from various stores… Due to the absence of any federal or state law addressing the issue, contract law governs the redemption process.”

“This is a criminal case, not a contract dispute,” prosecutors countered. “Mr. Balsiger seems to be suggesting that as long as IOS’s contracts did not explicitly prohibit IOS from misrepresenting or omitting relevant facts, such conduct was sanctioned and legal. He is mistaken.”

Besides, the prosecution says, the mixing of coupons alone is not the issue – the main issue is that “the vast majority of the coupons being diverted never had been redeemed at any store.”

The “Chop Crew”

Prosecutors plan to call more than two dozen witnesses, several of whom are expected to testify that most coupons that were diverted and mixed in with others “were ‘garbage’ and clearly had never been used at any store.” Instead, they were “gang-cut coupons” – coupons that a “chop crew” cut out from stacks of Sunday inserts, allegedly at IOS’s direction.

The leader of the coupon crew-for-hire will testify that he “had his employees obtain as many Sunday inserts as possible,” prosecutors said. “He would then mark the insert so that other workers knew what particular coupons should be clipped and falsely represented as having been redeemed at particular types of stores. The workers then were paid to cut coupons and prepare shipments of coupons that never had been used at a store.”

Manufacturers caught on to the alleged scheme when they noticed that thousands of coupons were submitted for reimbursement, from areas where the coupons were never distributed, by stores that didn’t even sell the products.

Balsiger counters that he’s the real victim, and that the chop crews were taking advantage of him. “IOS did not knowingly accept fraudulent coupons,” he insisted. “The government can, at best, only prove that IOS was the victim of a fraudulent coupon scheme.”

The Cement Mixer

So why would IOS employees stuff coupons into a cement mixer? Prosecutors say it was done to make mint-condition, gang-cut coupons look used – an improvement upon the old method of simply “having employees stomp on them”. It was also allegedly a way to mix up stacks of identical coupons submitted by the chop crews, in order to more evenly distribute them among the various collections of coupons submitted for reimbursement.

“The prosecution has no evidence or witnesses that any coupons in the cement mixer were not used by a consumer at the point of purchase,” Balsiger countered. He said using the cement mixer was “an intelligent solution” to a common problem – what to do with stray coupons that happen to get separated from the others as they’re all being sorted in a coupon processing facility. “It is common practice in coupon redemption to combine loose coupons (coupons on the floor, etc.) into a box or bin, stir those coupons so as to create a random sample, and then distribute/process those coupons on a proportionate basis of all the stores being processed through that plant,” Balsiger explained. He acknowledged that the cement mixer, which “was not owned or acquired by IOS but was temporarily left there by a construction contractor,” was an unorthodox tool – and it was only used for ten days before he put a stop to it.

Prosecutors dispute this explanation, and accuse Balsiger of encouraging a plant supervisor “to lie and say that the mixer was being used to destroy coupons from IOS’s former manufacturing division. Mr. Balsiger added that they could say they were experimenting with making pulp.”

Medical Mishaps

All of these arguments will be heard during the trial that’s expected to last for most of this month. But the proceedings nearly didn’t begin as planned, for the same reason that it didn’t begin as planned back in February. At that time, all parties had gathered in the courtroom for the first day of testimony when they realized that Balsiger was missing. He turned up in a local hospital, suffering from chest pains. The judge ultimately allowed Balsiger to return home to Texas to recuperate, and rescheduled the trial for October.

And last week, just days before the trial was set to start, Balsiger was hospitalized again. This time, he asked the judge to delay the trial by as long as three months. But the prosecution had heard enough. “Mr. Balsiger has sought to use his health to manipulate these proceedings,” prosecutors told the judge. “Mr. Balsiger has succeeded in delaying this trial beyond any limits that could have been imagined at the start of this case.”

Then they dropped a bombshell. After the February delay, “the FBI in El Paso occasionally conducted surveillance on Mr. Balsiger,” prosecutors revealed. Agents reported that Balsiger, who claimed he had “only a few years of life” left due to his “terminal heart condition”, seemed to be living that life to the fullest. They witnessed Balsiger visiting fast-food restaurants like Arby’s and Blake’s Lotaburger, hiking up a mountain, and running various errands. “He did not appear to be struggling as he had claimed to the court,” prosecutors reported.

The judge ordered an independent medical examination, after which he determined that the trial would commence as scheduled this week.

So after years of legal wrangling, both sides will finally be able to battle it out in the courtroom. Balsiger, who once famously described the entire coupon industry as a “lying, cheating, dirty business,” plans to fight what he calls a “false indictment” – and then sue his accusers in civil court. “While this may be my first experience in the criminal setting, I can assure you it will not be my first rodeo in civil litigation,” he wrote in a letter to one of the prosecutors. “You all have evidence that I am a litigious individual with an outstanding team of civil attorneys behind me. I can assure you that I not only thrive in that environment, but I love it.”

Those who have been waiting for a decade to see this case come to an end, should finally learn within the next several weeks whether Balsiger will pursue his civil case as a vindicated man – or as a federal convict.