Is it an issue of ensuring equity, or a commitment to fairness gone too far? One state has refined a proposal that would help marginalized people access digital coupon discounts, while another state is considering a proposal that’s so broad, it could change couponing as we know it.

That last measure is still on the drawing board. But the first is now one step closer to becoming law – the first of its kind to attempt to legislate a solution to couponing’s “digital divide.”

Nearly a year after it was first introduced, and with just weeks to go before the end of the legislative session, the New Jersey General Assembly has advanced a digital coupon bill out of committee. That sets it up for a potential floor vote, along with a vote on a companion bill in the state Senate, after which the measure could land on the governor’s desk for his signature.

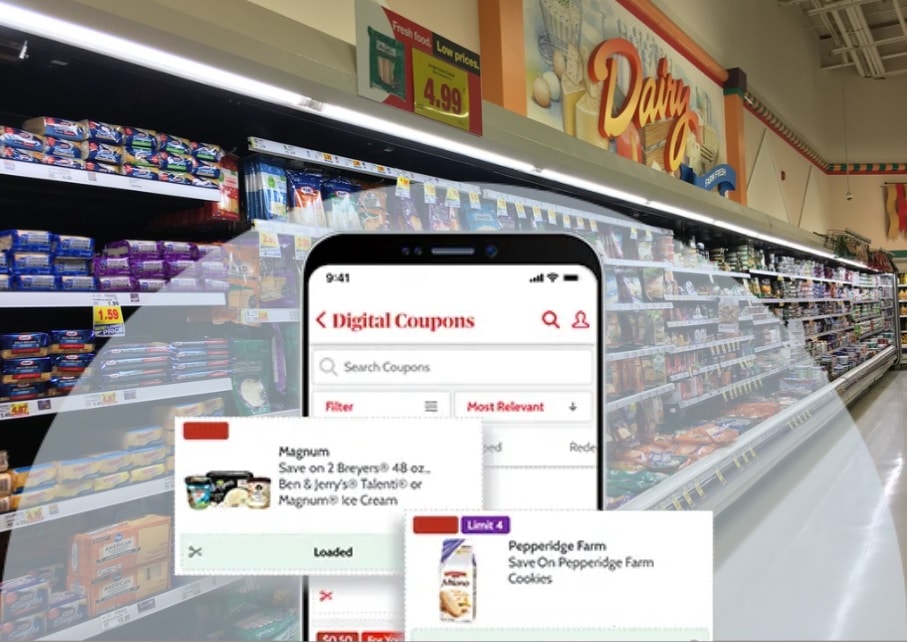

The bill would require anyone offering a digital coupon in New Jersey to make available an “in-store alternative of identical value,” for the benefit of elderly or lower-income shoppers who lack the means or the know-how to access digital coupons via a smartphone or a computer. That’s different than the version first proposed by Democratic state Assemblyman Paul Moriarty back in January, which initially required anyone offering a digital coupon “to also make available to a consumer a paper coupon of identical value.”

Moriarty told Coupons in the News at the time that he was open to input from the industry in tweaking the specific language of the bill. And retail groups spoke out about the difficulty of offering paper versions of every available digital coupon, particularly since it’s manufacturers and not retailers that issue most of them.

So the new version of the bill says any type of in-store alternative is acceptable, “including, but not limited to, paper coupons, electronic kiosks, or application of the discounted price or benefit at the point-of-sale upon the request of the consumer.”

Nevertheless, opponents who lined up to speak about the bill before members of the Assembly Commerce and Economic Development Committee this week still had a problem with it.

“We believe the legislation is well-intentioned. But we do have some significant concerns,” said Althea Ford, Vice President of Government Affairs at the New Jersey Business and Industry Association. She argued the bill’s phrasing is vague and unclear about whether it applies to retailers only, or also to manufacturers that offer digital coupons. “Our major concern is that if manufacturers are being told that they have to handle the offering of coupons in New Jersey differently than anywhere else in the country, then they will just opt to say ‘Not Applicable in New Jersey’ and call it a day, as opposed to having to go through the efforts to try to comply with this law.”

She went on to decry “the concept of government-mandated marketing.” “While we recognize and appreciate that the bill is viewing the topic of coupons through the lens of access,” she said, “we contend that coupons really should be viewed though the lens of marketing.”

Michael DeLoreto, the legal representative for the New Jersey Food Council, agreed. Coupons “are not meant to set a universal price for a product. Coupons are designed to bring about a sale that otherwise may not occur,” he said. “We need to recognize that coupons are advertising,” he continued, and “advertising is covered by the First Amendment.” So he expressed “concern about the ability of the government to step in and say, if you offer coupons through this means, you also have to offer it through another.”

Ford added that making every coupon available to anyone and everyone, could have the unintended consequence of lowering coupon values for everyone. The more people who have access to digital coupons via in-store means, the less money there is in manufacturers’ marketing budgets to provide all those discounts, she argued.

Moriarty rejected the critiques and wondered why the bill’s critics “think it’s okay to marginalize and discriminate against some customers over others.” Shoppers without access to digital discounts often need those discounts the most, he said. “This is a very simple bill. It’s about fairness. It’s about equity,” he explained. “If you’re going to make available a discount, and you’re only going to put it in a digital space, this bill says you have to find a way to have an alternative.”

And regarding the concern that making too many coupons available to too many people would lower coupon values, well, “that’s what happens when you make it democratic and you give it to everyone,” he said.

The three largest grocery chains in New Jersey are ShopRite, ACME and Stop & Shop. And each of them, to varying degrees, offers the very in-store alternatives as called for in the bill. ShopRite has in-store coupon kiosks where shoppers can load digital coupons to their loyalty cards before they shop. Stop & Shop recently began testing similar kiosks of its own. And ACME owner Albertsons told Coupons in the News earlier this year that “many of our stores also allow for individuals who may not have digital access to present the weekly circular to the cashier for the discount(s) to be applied at the register.”

Even those solutions don’t go far enough for Massachusetts state Representative Jeffrey Rosario Turco, though. New Jersey’s bill has inspired several identical bills in other state legislatures, including New York and Illinois. But Turco has introduced a version in Massachusetts that goes much further.

After stating that anyone offering a digital coupon must make available “a paper coupon of identical value,” his bill goes on to propose mandating that any and all digital coupon discounts be granted automatically for loyalty program members and senior citizens. Any retailer offering digital coupons “shall be required to apply said digital coupons to the purchases of any buyer 65 years old or older upon the presentation of a government-issued photo identification,” the bill reads. It goes on to say that “upon presenting a store card… the store shall apply all available digital coupons to the consumer’s purchase.”

So that bill doesn’t require shoppers to browse or clip digital coupons, or identify which offers they’d like assistance applying to their purchase – it just grants all digital coupon discounts automatically, whether a shopper is aware of their existence or not. Many shoppers might think this is a great idea. Retailers and manufacturers, who use coupons to incentivize purchases and not to give away discounts, are likely to think otherwise.

Turco’s bill is still in committee, however, and subject to the same kind of public comment and potential revisions as Moriarty’s bill was. And Moriarty’s revised bill, despite the concerns of those who spoke in opposition to it this week, was favorably voted out of committee. The Senate version of the bill was also voted out of committee earlier this year, which means the next step for both is a potential floor vote in the waning days of the legislative session. If both houses pass the measure, it could become law within weeks if the governor signs it, which will then give state retailers one year to come up with a way to comply.

“We want everyone to think about how they can come into compliance,” Moriarty said. “I believe they all can. I don’t think it’s rocket science.”

Whether you’re in favor of an activist government, or a critic of government overreach, the mere consideration of legislation does have a way of spurring the targets of that legislation into action. Since Moriarty’s bill was introduced, several retailers have publicly announced new ways for the digitally-disconnected to access digital offers in store. With New Jersey’s digital coupon bill potentially poised to become law, and with an even stricter bill in Massachusetts now under consideration, retailers may need to start considering how to make their digital coupons more accessible – or they may find they don’t have a choice.

Image source: ShopRite/Virginia Retail