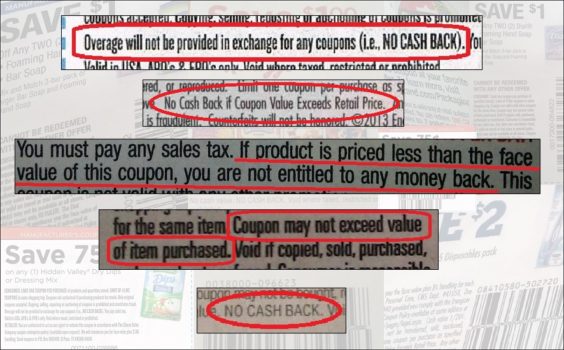

If you’ve read the fine print on your coupons lately, you’ve probably noticed more and more variations of the same new restriction: “Overage will not be provided.” “Coupon may not exceed value of item purchased.” “NO CASH BACK.”

At least ten CPG (consumer packaged goods) companies are now routinely including wording on their coupons that explicitly bans overage. What is this, some kind of conspiracy?

Apparently, yes. Many retailers and companies are determined to close the overage loophole that some couponers have long taken advantage of – and put that extra money into their pockets, instead of yours.

To the uninitiated, overage occurs when the value of a coupon is greater than the price of a product. Some stores, like Walmart, Publix and military Commissary stores, will accept all coupons at their full value, no matter the product’s price, and either apply any overage toward your balance or give you cash back. Many couponers consider this a nice perk, and a way to get a little extra discount on their total bill. Some who are more extreme, however, have been known to gather as many “moneymaker” coupons as they can get their hands on, buy only overage-bearing products, and essentially use their local store’s cash register as an ATM.

That’s why many more stores, like Target, Kroger, Safeway and the majority of other national and regional retailers, do not allow overage. They’ll “adjust down” the value of coupons at the register, so they don’t exceed the purchase price of the item they’re used on.

The dirty little (not-so-) secret, is that those stores usually get to keep any overage for themselves. Retailers typically attempt to maximize their reimbursements by submitting all coupons at their full face value, explained one industry insider who did not want to be named, while manufacturers in turn attempt to minimize their reimbursements by denying coupons that are improperly submitted. It’s something of a tug-of-war that each side tries to win.

Sophisticated point-of-sale systems can automatically adjust down coupons when they’re scanned, and record the actual purchase price in a transaction log. That, says another industry source, “allows the retailer to report this event to the coupon issuer, and at least theoretically, to process the coupon at the redeemed value instead of the face value.”

But in reality, that tends not to happen, and most retailers do get reimbursed the full value of the coupons that they adjust down. That means the manufacturers still end up losing money on their overage-producing coupons – they just end up paying that overage to the retailers, instead of to consumers.

So why would so many companies suddenly start adding coupon wording aimed at banning overage, if they have nothing to gain from it? It’s a good question – but one that most companies refuse to answer.

When Procter & Gamble began adding the sentence “No cash or credit in excess of shelf price may be returned to consumer or applied to transaction” to all of its coupons earlier this year, the company gave an amusingly convoluted non-answer to the simple question of, why?

Since then, other companies that had sometimes included such language on a few higher-value coupons, have begun adding a ban on overage to all of their coupons:

- Kellogg: “NO CASH BACK”

- Kraft Foods: “Consumer… will not receive any credit or cash back if coupon value exceeds purchase price.”

- Clorox: “Overage will not be provided in exchange for any coupons (i.e. NO CASH BACK).”

- 3M: “If product is priced less than the face value of this coupon, you are not entitled to any money back.”

- Reynolds: “Consumer… will not receive any credit or cash back if coupon value exceeds purchase price.”

- Boehringer-Ingelheim: “Coupons may not be redeemed for more than the purchase price of the product.”

- Henkel: “Coupon may not exceed value of item purchased.”

- Energizer: “No cash back if coupon value exceeds retail price.”

- Novartis: “Retailer: We will reimburse you for the lesser of the face value of this coupon or the retail price of the product.”

That Novartis wording, in particular, caused plenty of confusion when it first appeared last month on a pair of high-value coupons for $10 off 3, and $5 off 2 Prevacid, Gas-X, or Benefiber products. Overage-seeking couponers saw dollar signs in their eyes – until they saw the fine print.

Some shoppers reported that their usually overage-friendly stores wouldn’t give them any cash back when they bought the cheapest Prevacid, Gas-X and Benefiber products they could find, since their stores’ coupon policies contain a caveat (Walmart’s policy says “if coupon value exceeds the price of the item, the excess may be given to the customer,” and the Commissary says it “will give you the full face value of the coupon unless the manufacturer’s terms and conditions printed on the coupon prohibit it.”) Many other shoppers reported getting credited for the coupons’ full value, with overage, since the coupons were bar-coded to take $10 and $5 off, regardless of the products’ purchase price.

So why include the restriction at all then? Was it a notice to consumers that they shouldn’t expect overage? Or a notice to retailers that they had better not issue it?

Novartis refused to say. “We do not disclose our reimbursement agreements with retail partners,” a spokesperson said curtly to Coupons in the News.

That’s a pattern that recurred over and over again, as more companies issued overage-banning fine print, and refused to explain why. 3M “does not publicly comment on the reasons for these revisions,” a company spokesperson said. A Clorox spokesperson had “no information regarding the change in wording on our coupons.” Kraft answered with a non-answer (“coupons can only be redeemed when purchasing the product for which the offer was made.”) Reynolds, Henkel and Energizer did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Kellogg did offer a response, suggesting that the addition of the “NO CASH BACK” wording (and the equally popular “no more than four like coupons in a transaction”) was meant to deter overzealous shoppers who are more interested in overage than in their products. “We did this to help deter consumers from stacking coupons on top of trade deals and cleaning out the shelves,” a spokesperson told Coupons in the News. “Some consumers would even leave the product sitting in the grocery carts at the store after the transactions were completed and they had received the cash back. This caused problems as consumers who wanted to buy the product could not find it on the shelves.”

Boehringer-Ingelheim, maker of products like Zantac and Dulcolax, offered the fullest explanation of them all – suggesting that the addition of the phrase “coupons may not be redeemed for more than the purchase price of the product” was not solely the company’s doing – it was at the behest of retailers.

“The coupon language was changed in partnership with our retailers to reflect that consumers should receive a discount on the price of the product up to the face value of the coupon,” a Boehringer-Ingelheim spokesperson told Coupons in the News. “This is intended to prevent misuse of our coupons and to comply with retailers’ requests to prevent disputes with consumers at the point of sale.”

Consider that another dirty little secret about coupons – retailers are not mere passive recipients of whatever coupons that manufacturers decide to issue. They can have a say in everything from the language, to the value of the coupons issued.

“The marketing departments at larger CPGs tend to be structured vertically into their major retail customers, which means that retailers are talking directly with marketers,” explained the industry source. So “it is certainly possible that the language originated from a retailer request.”

Such “retailer requests” may also be behind coupons that say “do not double”, or are valued at 55 cents instead of 50 cents (the upper limit of many stores’ double coupon policies). Neither offers any real benefit to manufacturers, but it can certainly help out retailers, who may want to wiggle out of their double-coupon promise for certain offers.

So the real reason that so many coupons are banning overage lately? Apparently some stores no longer want to have to explain or defend their own overage-banning coupon policies. If you question why your coupons aren’t being accepted at their full face value, the store can just point to the coupons’ fine print and blame it on the manufacturer. And as an added perk, they get to keep the overage for themselves, with the manufacturer’s tacit blessing.

“The intent of most coupons is to cover up to only the actual price of the product,” the Coupon Information Corporation advises consumers. “Overage is an unusual situation and you should not expect to receive cash back on the purchase of a product.”

Of course, if manufacturers and retailers are really determined to deny overage, the coupons could be worded and coded to apply only to certain products. A Crest coupon that says “excludes trial/travel size” is easier to understand, and to code, than a coupon for 25 cents off Charmin that laughably states “no cash or credit in excess of shelf price” (hey, don’t spend all the overage from that generous coupon in one place!) Our industry insider suggests that manufacturers could focus on coding their coupons to apply to specific products, instead of adding yet more fine print that amounts to nothing more than a difficult-to-enforce recommendation or disclaimer.

But back to those Novartis coupons for $5 and $10 off Prevacid, Gas-X and Benefiber – some shoppers said they didn’t get any cash back, others did, but many more saw the fine print and decided not to bother even trying for any overage.

And that, a growing number of manufacturers and retailers hope, is precisely the idea.

Pingback: Target Coupon Update Change for the better 2016 - Saving A Buck with Mrs. Buck