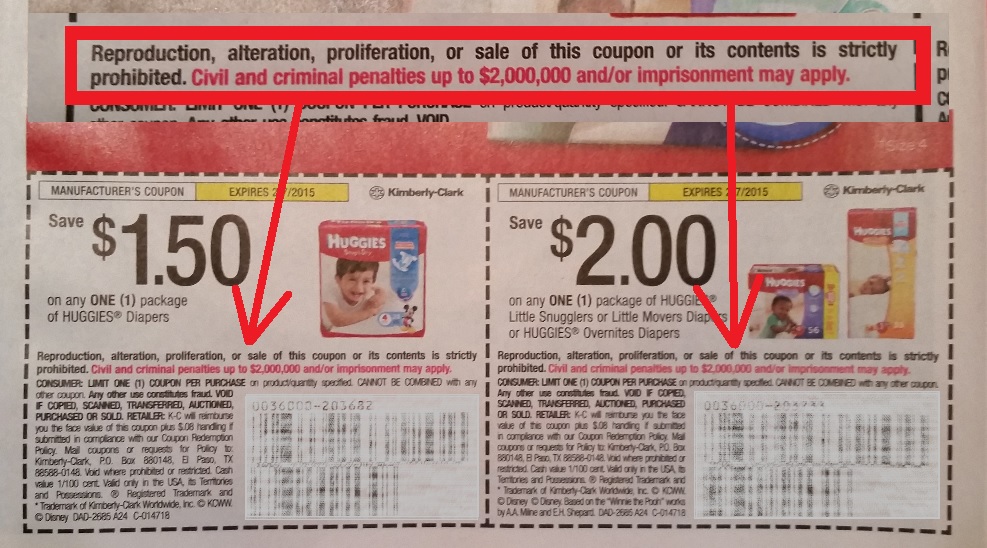

You may not pay much attention to the fine print on your coupons as you flip through your Sunday inserts, but the new wording on Kimberly-Clark coupons in this past weekend’s SmartSource was designed not to be missed. “Reproduction, alteration, proliferation, or sale of this coupon or its contents is strictly prohibited,” the coupons for products like Kleenex, Cottonelle and Huggies now read. And then, in bold red type: “Civil and criminal penalties up to $2,000,000 and/or imprisonment may apply.”

It’s another sign that coupon issuers are getting serious about combating coupon fraud. But what precisely does this new warning prohibit? Which of the listed transgressions could get you in that much trouble? Are you in danger of being thrown in the pokey for buying coupons online?

And what the heck is “proliferation” of a coupon?

As typically happens any time companies add new legalese to their coupons, Kimberly-Clark isn’t saying much beyond what’s on the coupons. “This statement highlights several aspects of improper coupon activity and attendant risks,” Kimberly-Clark Consumer Promotion Manager Jodi Gennrich told Coupons in the News.

But is the wording meant to suggest that selling a coupon is now considered just as bad as counterfeiting it? Where does that $2 million figure come from? And worst of all, what if you accidentally “proliferate” a coupon and don’t even know it?

“We are not at liberty to comment further on potential legal aspects of the statement,” Gennrich said.

It’s up to coupon users, then, to interpret the new wording themselves. And that’s kind of the whole idea.

So let’s take a closer look at that warning against “reproduction, alteration, proliferation, or sale of this coupon.” It goes without saying that coupons should not be reproduced, altered or forged and created yourself. That’s counterfeiting, and that’s illegal. So the fine print on coupons has long warned against counterfeiting. But with more than 400 Kimberly-Clark coupons currently on the Coupon Information Corporation’s counterfeit alert list, you can’t blame the company for wanting to call a little extra attention to coupon counterfeiting, and the risks that it poses.

Under federal law, $2 million is the maximum fine a first-time offender faces for trafficking in counterfeit goods – whether it’s Rolex watches or coupons. It’s also the maximum fine for committing trademark infringement. So a victimized company could conceivably go after a coupon counterfeiter for either offense, each of which also comes with a maximum ten-year prison sentence.

As for “proliferation”, that presumably refers to reproducing a coupon in mass quantities – the difference between photocopying a single coupon, and running your own coupon printing press. But only Kimberly-Clark’s attorneys know for sure – and they’re not telling.

That leaves selling insert coupons. Could that also land you in the big house, on the hook for $2 million?

Well, no. But Kimberly-Clark’s coupons sure make it sound that way, don’t they?

People who sell clipped coupons and whole inserts online have long been a thorn in the side of coupon issuers, and the practice remains a controversial one among coupon users as well. If the purpose of a coupon is to entice you to try a new product and eventually become a full-price-paying customer, the sale of coupons throws a wrench into that plan. Selling coupons serves to redistribute mass quantities of like coupons to a single user, who ends up purchasing mass quantities of discounted products at a loss to the manufacturer, and never becomes a full-price-paying customer.

It’s bad for the manufacturer, good for the consumer – until the manufacturer can’t afford to issue coupons anymore. Then it ends up being bad for all consumers.

And therein lies the controversy over whether coupon selling is harmless or harmful. Coupon issuers don’t like it, so they’ve made lots of attempts to stop it. Their fine print insists their coupons are “void if sold”. They’ve pressured websites like eBay and Facebook into cracking down on the sale and misuse of coupons.

The only problem is, there’s no law against it. Counterfeiting coupons is illegal, yes, but however undesirable coupon selling might be, no one’s ever been arrested for reselling legitimate coupons. And how many resold coupons do you think are actually refused at the checkout because they’re “void”?

That’s emboldened coupon resellers to continue their work, then, despite the industry’s best efforts to stop them. So why not try something new, Kimberly-Clark no doubt figured, like conflating several undesirable activities into one long list of no-no’s, so it seems like they’re all illegal and punishable by jail time and a $2 million fine – without actually saying so?

Clever.

Of course, that’s not to say that all coupon sellers are in the clear. Many “clipping services” have been known to offer too-good-to-be-true counterfeits (and some have indeed been fined millions and served jail time). And many sellers with stacks and stacks of coupon inserts for sale didn’t get them all by buying newspapers.

Kimberly-Clark’s new fine print debuts as the coupon industry is in the midst of an effort to find the source of stolen coupon inserts that end up for sale. But it’s not a concerted effort. “Use of this statement was not coordinated with other industry groups,” Kimberly-Clark’s Gennrich said.

So when it comes to activity that coupon issuers find objectionable, they can launch investigations, they can pressure others who enable the activity – and they can put ambiguous wording on their coupons in the hopes of scaring off impressionable resellers. If that helps to make coupon selling a topic of conversation, and changes the tide of public opinion against the practice – it just might prove to be the most effective tactic of all.

If there is no prosecution of ‘offenders’, what exactly is the point of the CIC which in the past has made it sound as though it was a crime to exchange or give coupons to those who would use them? In past research (about 15 years ago), manufacturers were discussing whether or not to continue publishing coupons or lower the prices of their products so that the items would be purchased. At that point they stated that thought they would save money by not printing the coupons, the prices would not be dropped if the coupons stopped.