Coupons are great when you don’t have to search for them. Someone might hand you one in the store, or they just show up in your mailbox or your driveway. Easy savings! But a new study says the best coupons are the ones you have to work for – and the more effort you have to expend, the better they get.

That’s the conclusion of a new research report published in a recent edition of the Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. “Effort justification for fun activities? The effect of location-based mobile coupons using games” examined whether we value coupons more when we have to work for them – particularly when that “work” is fun.

Previous studies that the researchers cite have found that “offering free coupons is not a good idea.” The thinking is that “when customers receive coupons without doing anything, they may experience a cognitive dissonance between the amount of effort exerted to obtain the coupon and the perceived value of it.” In other words, anything you get for free can’t possibly be valuable or desirable, but if you have to do some work to get it, it must be worthwhile.

The researchers therefore decided to find out whether “certain tasks should be given so that customers can justify the value of the coupon.”

So they recruited volunteers, and offered them a mobile coupon for 50 cents off a purchase at an office supply store. Some research participants were just given the coupon, no strings attached, others had to complete a survey first, and others were asked to play a mobile game in order to “win” the coupon as a prize.

And the researchers found that those who were just given the coupon thought it was okay, those who completed the survey thought more highly of it, and those who played the game were more pleased with their coupon and more likely to use it than anyone else in the study.

Why? Because “games are fun,” the researchers explain plainly. “When an activity is fun, humans are intrinsically motivated,” which produces a “positive affect that can further enhance the perceived value of the promotion.”

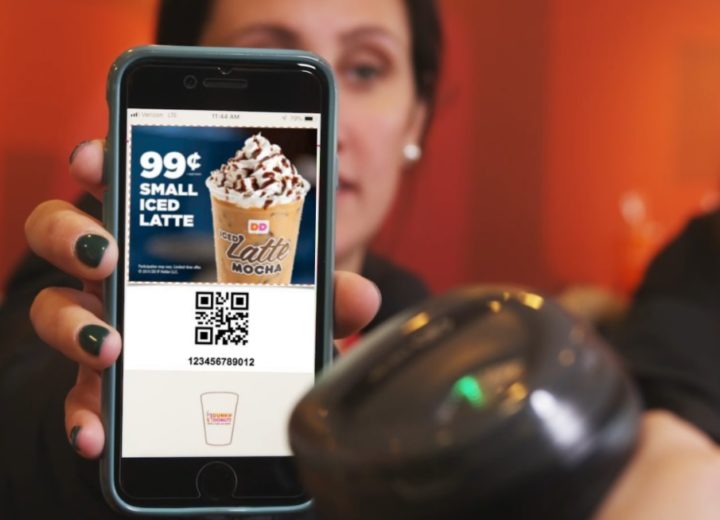

Interestingly, the researchers then tried something else. They changed the coupon offer from a discount on office supplies, to a coupon for 50 cents off a donut at Dunkin’ Donuts. Volunteers were again given the coupon for playing a game, completing a survey, or doing nothing. Those who did nothing were again the least likely to think highly of the coupon. But in this case, the survey-takers liked the coupon more than the game-players.

The reason? One word: guilt. The researchers concluded that the coupon recipients were better able to justify playing a fun game to earn a discount on a dull product like office supplies. But playing a fun game to get a fun product like a donut was a little too much, psychologically speaking. Indulgences like donuts “involve feelings of guilt,” the study found. Coupon recipients could justify playing a fun game if they could earn a useful reward for doing so. But in the case of the donut, “the positive emotions activated from the fun and enjoyable experience of a game may hinder the justification of consumption.”

So what can we learn from this – should every marketer start making us play games to save a few cents on printer paper, or take surveys for a half-priced donut? The researchers caution that it may not always work. “When a coupon is obtainable only after completing a task requiring some level of effort, customers may experience negative affect.” You may value a coupon if you have to do some work to get it, but could you imagine having to complete a task to “unlock” each and every offer in your Sunday coupon inserts or your store’s digital coupon gallery?

The study authors also point out that their research specifically involved mobile coupons, which can be location-based and delivered when you’re at or near a store, they can be sent at a specific time of day, or personalized to make them more relevant. If you’re standing outside a Dunkin’ Donuts mid-morning, and get a notification on your phone to play a game to get a coupon that you can use right away, you may be more pleased and more likely to use the coupon than if you’re sitting at home late at night, reading a paper flyer inviting you to play a game in order to receive a paper coupon in the mail that you’ll need to drive to the store to redeem.

Study or no study, some marketers are already catching on to the idea of game-based coupons. Consider how many people spent an hour or two of their time playing an intentionally-boring video game last month just to get a coupon for a free sandwich. Having to play a game to save on each item on your grocery list may be asking too much. But as a one-off, it’s something to consider. After all – who ever said saving money couldn’t be fun?

Image source: Dunkin’/FunMobility