In some ways, it seems like coupon inserts have always been a part of your Sunday newspaper. In other ways, it’s hard to believe that coupon-clipping has been a Sunday ritual for so long. Either way, this month marks a noteworthy milestone – the 50th anniversary of the free-standing coupon insert as we know it today.

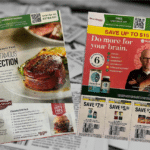

It was in August of 1972 when Michigan printer George Valassis offered what was to become the first regularly-published, multi-brand coupon booklet, featuring a selection of discounts off a variety of grocery products, appearing alongside other ads and flyers inserted into Sunday newspapers (an early version of the Valassis insert is pictured above, at left). By the following year, Valassis had drawn up a full schedule of planned publication dates, so manufacturers could plan their promotional campaigns for the year ahead.

And from there, an industry was born.

While coupon inserts as we know them today might not exist without Valassis, the earliest origins of the concept go back a little further. Other printing-press operators had discovered that offering their services to grocery brands to print their coupons was a good way to drum up some additional business. Before then, coupons would often be printed on the pages of newspapers and magazines alongside other ads. Printing entrepreneurs like Ted Isaac of Kansas saw the value of combining those coupons into a single publication, providing a one-stop shop for coupon clippers.

“Long before Steve Jobs, Ted launched the newspaper insert industry from his garage,” Isaac’s 2016 obituary read. “I’m the father of an industry,” he boasted to the New York Times decades earlier. Back in the late 1960s, Isaac’s Consumers Circulation Company began offering what he called “Happy Days” and “Flagwaver” inserts. Happy Days was simply an envelope stuffed with coupons, inserted into newspapers. The Flagwaver was a heavy-stock, one-sheet ad featuring four coupons cut along the side of the page that “waved like flags.”

Valassis’ early inserts adopted the flagwaver format. And while Isaac’s business eventually waned, Valassis stuck with it, as increasing demand turned what was a single-sheet flagwaver into a multi-page booklet as we know it today.

“Publishing a set schedule and market list in 1973 turned out to be a pivotal decision,” an early company history explained. Manufacturers like Colgate and General Foods were among the first to offer coupons in what Valassis described as “a cost-efficient, four-color vehicle that can deliver coupons to millions of people in a single day.”

“This efficient format and process kicked off the coupon culture in America,” Debbie Gauthier, Executive Director of FSI & Neighborhood Targeted at Valassis’ present-day parent company Vericast, told Coupons in the News.

Competitors came and went over the years. But while ownership of Valassis has changed several times, and the name of its inserts has changed from Valassis to RedPlum to RetailMeNot Everyday to Save, its legacy of printing coupon inserts is the longest-lasting of any company by far.

But a lot has changed over the past half-century. And change has been accelerating in recent years, with newspaper distribution declining sharply and more coupons migrating to digital formats. So does the coupon insert as we know it have another half-century of life left?

Kantar’s recent midyear figures showed that the number of coupons available is continuing a years-long decline, led by a sharp and ongoing downturn in the number of newspaper insert coupons. And it doesn’t help that major manufacturers like General Mills and Procter & Gamble have stopped offering insert coupons altogether for some or all of their brands.

But Vericast is confident we’ll be seeing Save coupon inserts for some time to come. “Distribution was about 18 million homes in the early days of the company. Last year, Vericast distributed to more than 55 million total households,” Gauthier pointed out. As newspaper distribution has declined, Vericast has increasingly pivoted to alternate distribution methods, like direct mail and home delivery, to ensure that its coupons are still received by coupon-hungry households.

“We believe in this strategy as a viable solution for our client partners,” Gauthier said. “Consumers actively sought coupons back then as they do today.”

That said, there’s no denying that the coupon business is changing. Back in the 1970’s, George Valassis simply printed coupon inserts out of his suburban Detroit home. Later, the company tried diversifying into in-store coupons, and print-at-home and digital coupons. While those initiatives didn’t last, Vericast is now working to help pioneer what supporters are calling the true future of coupons.

“From its onset, Vericast has played a significant role in developing the new Universal Coupon standard,” Gauthier said. Earlier this year, the company revealed plans to begin offering this new form of digital coupon, which can be downloaded to your mobile device and scanned right off your screen. It’s an improvement on load-to-card digital coupons, which have to be redeemed at a specific retailer, or print-at-home coupons, which are accessed online but have to be redeemed in paper form. Vericast hopes this new type of coupon will supplement those offered in its legacy coupon inserts. “As adoption of Universal Coupons grows, Vericast plans to offer consumers downloadable Universal Coupons on its Save.com website,” Gauthier said.

As for coupon inserts themselves, the format as we know it is now entering its second half-century. In these days of digital everything, the idea of printing paper coupons and hand-delivering them to homes across the country may seem outmoded. But the system has endured, as advertisers continue to find it an efficient and affordable way to reach tens of millions of shoppers every week of the year.

The concept of the coupon itself was invented well over a century ago. Can coupon inserts hit the 100-year mark too? Well, check back in about 50 years to find out.

Historical coupon insert image provided by Vericast

we don’t get Save coupons in Philadelphia