So will the proposed Kroger-Albertsons merger really be as good for customers, employees and communities as the two grocery chains claim? That’s what a skeptical and at times cynical Senate panel wanted to know, as the architects of the deal found themselves in the hot seat yesterday, answering pointed questions about how decreased competition could possibly be better for consumers.

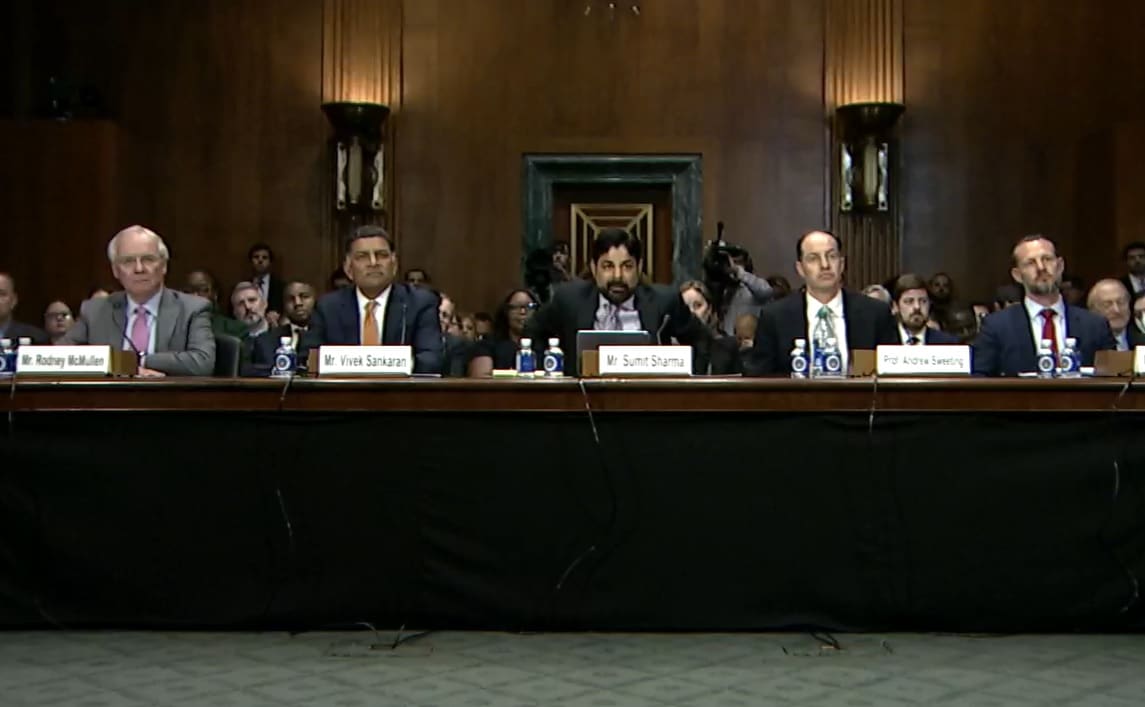

Just over six weeks after Kroger, the country’s largest traditional grocery chain, announced a $24.6 billion bid to acquire Albertsons, the country’s second-largest traditional grocery chain, the CEOs of both retailers testified about their planned deal before the Senate Subcommittee on Competition Policy, Antitrust, and Consumer Rights. Appearing alongside an economist, a consumer advocate and an independent grocery owner, Kroger CEO Rodney McMullen and Albertsons CEO Vivek Sankaran made their case as to why their proposed merger is nothing for shoppers, workers and government regulators to worry about.

“Through this merger, we will invest in lower prices and give customers more choices,” McMullen insisted. Joining forces with Albertsons will allow the combined company “to more effectively operate in the constantly evolving and fiercely competitive grocery landscape,” against the likes of Walmart, Amazon and Costco. Operating efficiencies will allow the grocers “to invest $500 million to lower prices and $1.3 billion to improve the customer experience,” making the merger “a win for customers, a win for associates and a win for American competition.”

“We determined that the best way to compete directly against megastores like Walmart and highly-capitalized online companies like Amazon, would be through this proposed merger with Kroger,” Sankaran added. A combined Kroger-Albertsons would be a stronger competitor that “will help protect the local community grocery stores that people love.”

Senators on the panel appeared unconvinced. “A lack of competition in the industry means higher prices and lower quality,” Democratic Senator Amy Klobuchar, the Subcommittee Chair, said. Consider the small city of Florence, Oregon, whose residents can choose between two supermarkets. “Your options are to shop at Fred Meyer, owned by Kroger, or at Safeway, owned by Albertsons. These two stores have to compete for business, meaning they will offer lower prices,” Klobuchar said. “Now if those two stores are operated by the same owner, there’s no incentive to compete for customers and prices. They might even close one of the stores.”

Ranking Subcommittee member Republican Mike Lee noted that the merger proposal comes at a time of high grocery prices and record profits for grocery retailers. “Earlier this year,” he said, “McMullen confessed that ‘a little bit of inflation is always good in our business.’ Well, it must have been very good this year, as Kroger has now amassed enough to spend $24.6 billion to buy up one of its largest competitors.”

Senators weren’t the only skeptics in the room. Consumer Reports senior researcher Sumit Sharma also testified. “The claimed efficiencies are uncertain,” he said, and “will not necessarily be passed on to consumers.” He cited Consumer Reports research that found Kroger and Albertsons “have a much higher percentage of product ranges on promotion.” While less than a quarter of products are on sale at any given time at stores owned by Ahold Delhaize, Amazon Fresh and Publix, more than a third of products are on sale at Kroger during that same time, while more than half of Albertsons’ products are. A merger “is likely to reduce incentives to offer these higher promotions,” Sharma said, “as Kroger will no longer face competition from Albertsons and vice versa.”

Even if a combined company can reduce expenditures by eliminating overlap and taking advantage of greater purchasing power, “why would any of those savings be shared with consumers unless competition incentivizes the parties to do so?” Sharma wondered. “These are, after all, profit-maximizing corporations.” His conclusion was that “the transaction will result in significantly lessening of competition, and the most likely outcomes are higher prices, fewer choices, and reduced access to supermarkets for some consumers.”

Michael Needler, the CEO of independent grocer Fresh Encounter, also testified on behalf of the National Grocers Association. “We are agnostic on this transaction,” he insisted, but he raised a number of concerns nonetheless. Big buyers are better able to squeeze concessions and promotional allowances from suppliers, which allows them to sell groceries at lower prices. Smaller, independent grocers don’t get that kind of consideration, so their shelf prices can end up higher than the big national chains’. “Big isn’t always bad,” Needler said. “However, the Kroger-Albertsons merger is on a different order of magnitude, so it warrants strong antitrust scrutiny.”

The specter of the 2015 Albertsons-Safeway merger, and its unfortunate fallout, hung heavy over the hearing. Albertsons was required to divest 168 stores in order to gain Federal Trade Commission approval for that deal. It sold most of them to the small regional grocer Haggen, which promptly went bankrupt, closed most of the stores it had acquired, sold most of the rest back to Albertsons and – in the final indignity – was itself acquired by Albertsons. Cynics said the entire saga made a mockery of the FTC order aimed at preserving competition, which instead consolidated the industry even further.

“If this feels like déjà vu all over again, that’s because it is,” Lee said. As part of their merger agreement, Kroger and Albertsons have proposed divesting anywhere from 100 to 375 stores in markets where the two grocers overlap, spinning them off into a separate standalone company they envision as “a new, agile competitor.” But Lee and others wondered if that “new, agile competitor” could just become another Haggen. Incidentally, Lee pointed out, “the FTC official who had signed off on that (Albertsons-Safeway) divestiture now runs the antitrust practice at the law firm representing Kroger in its purchase of Albertsons. Hollywood couldn’t write a more cynical plot, not if it tried.”

Sankaran defended the Albertsons-Safeway merger as being a success – if you look past that whole Haggen thing.

McMullen, meanwhile, found himself defending his plan to lower prices post-merger. Not doing so, he said, would be bad business. “Our business model is built around lowering prices to attract more customers,” he insisted. “If we do not provide value and quality, customers will shop somewhere else.”

But when Republican Senator and subcommittee member Marsha Blackburn asked how the proposed $500 million in customer savings will manifest itself – in the form of lower prices across the board, or a greater investment in coupons, or more personalized prices to select shoppers? – McMullen didn’t offer details. And he acknowledged there’s no way to hold him to his promise. But “our history of mergers shows we follow through on our commitments,” he said. “Following our merger with Harris Teeter in 2014, we lowered prices by $130 million per year. After our merger with Roundy’s in 2017, we lowered prices by $110 million per year.”

In the end, there’s not much the Senate subcommittee can do to hold the grocery executives to their promise that their merger will be a good thing for all involved. The hearing was just a fact-finding mission, and an opportunity for lawmakers to weigh in. The real scrutiny will come from the FTC, which will ultimately decide whether to approve, deny or modify the proposed merger. Only then will we find out for sure whether more competition – or less – is truly better for your grocery budget.

Image source: Senate Subcommittee on Competition Policy, Antitrust, and Consumer Rights